A negative German trial?!

The Arthorad trial (Niewald et al)

So now onto the Arthorad trial. This was a comparison of 3Gy in 6# (0.5Gy/#) vs 0.3Gy in 6# (0.05Gy/#). You may ask why they didn’t just use a sham arm like the Dutch. And this has a historical and cultural background: LDRT is so embedded as a standard treatment option in Germany that it was felt that patients wouldn’t accept (and perhaps wouldn’t be funded for) a sham (0 Gy) arm. So the control arm was a “tiny” dose of radiation.

Both groups showed significant improvement in pain and function, but no difference between the two doses. My own reaction when I first read the results was disappointment that this was a negative trial. But the conclusion in the paper said:

“We found favorable pain relief and a limited response in the functional and quality of life scores in both arms. The effect of low doses such as 0.3Gy on pain is widely unknown. Further trials are necessary to compare a conventional dose to placebo and to further explore the effect of low doses on inflammatory disorders.”

Personally I found this statement a bit disingeneous, as the alternative explanation is that this is just a negative trial. In particular, if 3Gy turned out to be better than 0.3Gy, would they have reported this as negative, or would they have said that 3Gy is better than control? Draw your own conclusions, but if we take their statement at face value then there is indeed a chance that 0.3Gy could be just as effective as 3Gy. More on that when we come to the South Korean trial.

The Iranian Trial

Some Positive Results at last!

In 2025, an Iranian group (Fazilat-Panah et al.) reported a double-blind randomised trial in 60 patients with knee OA, comparing 3 Gy over six fractions with sham treatment.

Patients were Kellgren-Lawrence grades 1–3, and outcomes were measured with VAS and Lysholm scores at baseline and monthly up to six months. Interestingly they gave the treatments daily, rather than the more standard way of doing it with at least 48 hours between each fraction.

This study was positive: the radiotherapy arm showed significantly better pain and function scores at every follow-up point. Analgesic use decreased, and patient satisfaction was high.

So what do we make of the discordance between this trial and the Dutch trial. Well, in a number of aspects the trials are very similar – a small trial, sham controlled. A few small differences – more “modern” total dose of 3Gy/6#, but an unusual fractionation scheme as the dose was given daily. Also quite an old population (lowest age = 72 years), and not amazing reporting of e.g. BMI, duration of symptoms.

But an actual positive trial at last!

The Korean LoRD-KNeA Trial

Positive trial, reported at ASTRO in August

So this is a really interesting trial, which took into account the information from the Arthorad trial in its trial design and tested 3Gy/6# vs 0.3Gy/6# vs 0Gy/6#. So the questions it asked were:

1. Is radiation better than placebo?

2. Is 0.3 Gy total dose enough?

Patients had knee OA Kellgren-Lawrence grade 2–3 and baseline VAS pain score 50–90/100. Analgesic use was restricted to paracetamol. Follow-up was four months, and outcomes were measured using the OMERACT-OARSI criteria, which is a robust and well-accepted outcome measure.

And this trial was positive – 3 Gy was significantly better than sham, although 0.3 Gy was not. The investigators didn’t show the 3 Gy vs 0.3 Gy comparison, which would have been interesting given the Arthrorad results (see above), but overall this trial confirmed that radiotherapy at conventional anti-inflammatory doses provides real benefit.

One point that was made in the ASTRO session, which I think is very valid, is that the patient cohort was relatively healthy and metabolically lean compared to US populations (especially those with OA), so there remains a question about generalisability.

The Russian Trial

Bigger numbers, longer follow-up, objective outcome measures

Alongside these newer trials, the Makarov et al. study from Russia provides valuable long-term data. If you’ve never heard of this trial then you are in good company as the results have been published in highly obscure journals and much of it isn’t even in English. But despite that it really is an amazing trial which provide some quite ground-breaking data. So here goes…

300 patients were randomised to receive standard glucosamine/chondroitin therapy (SYSDOA) with or without low-dose radiotherapy. The radiotherapy dose was 0.45 Gy per fraction for ten fractions (total 4.5 Gy, treatment given on alternate weekdays). Patients were much younger than in other trials (mean 35–40 years old) and had earlier OA (K-L 0–2). Follow-up extended to 10 years.

Results showed sustained improvements in pain, function, and quality of life, as well as MRI evidence of reduced synovial inflammation, bone-marrow oedema, and osteophyte progression. Even arthroplasty rates were lower in the RT group, though not statistically significant due to small event numbers.

So lets have a think about this. Young patients with painful OA, but lower stage than in other trials. And it showed that rates of pain, disability and objective structural joint deterioration were reduced. So it brings us away from simple pain relief and functional improvement towards a different conclusion:

“Radiotherapy can actually change the long term course of osteoarthritis”

Now to me this is a bit of a wow moment. Radiotherapy, by its biological action, can stop OA getting to the stage where you become disabled and where you need surgery. [Dare I ask: Should we be screening for this and treating patients prophylactically?!]

Putting this all together

Three positive trials (Iran, Korea, Russia) now outweigh one small negative Dutch study.

Evidence quality is improving, and structural benefits are beginning to emerge.

Knee OA remains the best-studied and most practical benign musculoskeletal indication for radiation oncologists to adopt.

Patient selection, technique standardisation, and data collection are key to success (see practical tips below).

Ongoing trials

It’s worth being aware of two more randomised trials that are still ongoing:

Mayo Clinic: low-dose RT versus sham for knee OA. This is highly important as testing it in a presumably metabolically more compromised US population will deal with criticisms about testing the treatment in an inappropriate population.

Erlangen, Germany: IMMO-LDRT2, across multiple joints including the knee. Also has radiobiological and immunological aspects to the study.

And you should be aware also of an “exotic” (to my mind anyway) and positive trial of radium bath treatment vs. warm water baths in patients with “musculoskeletal disorders” from Erlangen, Germany.

Translating the Evidence into Practice

For radiation oncologists building benign radiotherapy services, knee OA is a perfect entry point. It’s common, technically straightforward, and well supported by emerging RCT data.

Here are the key practical lessons:

1. Patient Selection

Ideal candidates have:

Kellgren-Lawrence grade 2–3 OA (you can treat lower KL, but you are much less likely to get an effect in grade 4 disease)

Pain at least 4 – 5/10 VAS

Pain refractory to conservative treatment for at least 3 – 6 months

Symptom duration – shorter is better

Dose: 0.5 Gy per fraction, 2-3 fractions per week, six fractions (total 3 Gy). I’ll write a future detailed post on dose-fractionation, assessing response, and how to decide on a second phase and at what dose.

Orthovoltage or LINAC techniques are both acceptable

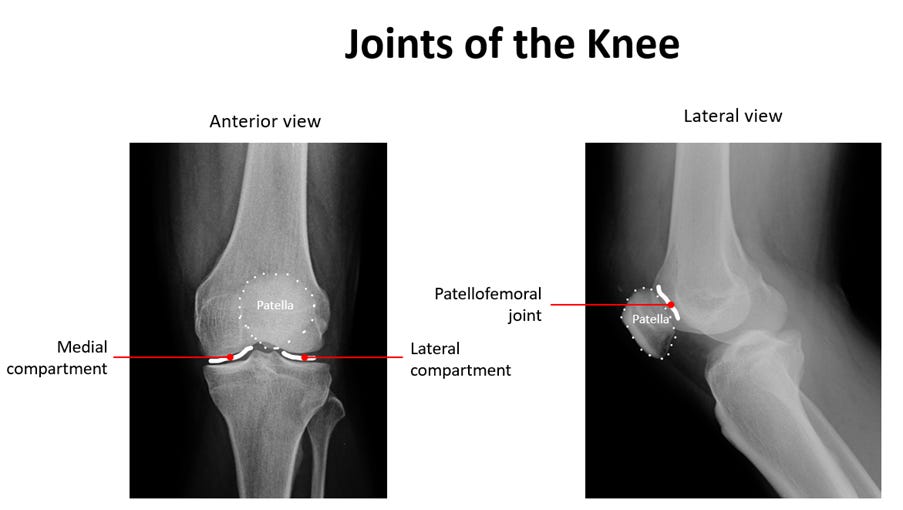

Be aware that the target is NOT the joint + a margin. Often (but not always) it’s the synovial sac. I’ll also write a detailed post on this soon.

We tend to use a parallel pair of photons (two laterals or AP/PA)

Record baseline and follow-up pain & functional scoring at 3, 6, and 12 months

Establish a simple outcomes database – this will help build credibility within your department and local referral network.